FYEO Debriefs ‘I Spy’ Star Robert Culp

Outspoken actor and writer Robert Culp will, after a 25-year layoff, once

again be seen as Kelly Robinson in “I Spy Returns.” In December, he’ll

appear as the president of the United States in “The Pelican Brief.”

FYEO Contributing Editor Jon Burlingame recently spoke to Culp

about the I Spy series and revival.

FYEO: Everyone who talks about I Spy remarks on the “chemistry” between you and Bill Cosby. Was it there from the beginning?

CULP: From the first hour? No. The first hour was strange and awkward. We went over [to Hong Kong] and made this so-called test film that was allegedly to be the pilot, a dreadful film, “Affair in T’sien Cha.” God almighty, it was so bad it had to be buried Christmas week of the first year. We did that, and on the way back on the plane I remember being very depressed, because I said this thing is never going to fly. These guys [producers Mort Fine and David Friedkin] can’t write it, it’s just too stiff and too stoic. Then I found out something very interesting, something I’d never heard of before. Sheldon [Leonard, I Spy’s executive producer] had 13-firm, no-pilot. Oh, but Sheldon you’ll make a little test film, which is why we went to Hong Kong. Nobody had that kind of deal. It indicated immense power on his part and belief in him on the part of the network.

I went to him and asked him, are you going to make all these shows? He said, I’m going to make all 13 no matter what happens. I said, boss that’s all I need to know. I went home, and I didn’t tell a soul, and I sat down and wrote my first four. One of which became the pilot, “So Long, Patrick Henry.” But the first one I wrote was called “The Loser,” it starred Eartha Kitt and Bill, and I took a back seat. I think “Patrick Henry” was the third one out of the four.

This took four months to write these four. I took four months off out of my life, locked the doors and stopped talking to my wife and children. Literally turned the phone off, I wouldn’t talk to anybody. I banged on it as hard as I could, trying to find the tone that I could repeat, that I understood, that I could relate to, that I knew Bill could come to with me, because he wasn’t seasoned as an actor yet, and we could play around with it, and still the stories were strong enough underneath to carry us no matter what happened. Which is what was wrong with “Affair in T’sien Cha,” the story was very weak. And it didn’t carry us, and as a consequence, we fell down.

The only person I spoke to was Bill. I found him on the road and we talked every single day. He would call me or I would call him, from wherever he was on the road doing comedy clubs or television appearances. We made it our business to talk to each other once a day. Sometimes for 10 minutes, sometimes for an hour. And in the process of all this, “The Loser” was getting formed. And I sent it to him on Valentine’s Day, as a Valentine’s present in 1965. And I said, it’s comin’ at ya, read it carefully, this one is important to you.

That was probably the fifth or sixth show we shot. And this man is the quickest study who ever lived. No one has a faster mind than Bill Cosby. He was wonderful. He won his Emmy that year off of that script. Eartha got nominated, I was nominated, the show was nominated. And that’s when we really began to coalesce as one.

FYEO: I’ve always been curious about how the series worked on a practical basis, shooting exteriors overseas then returning to Hollywood to complete groups of episodes.

CULP: The deal that was struck with IATSE was they would permit us to go abroad and film exteriors for nine shows. Meaning we had nine shows in advance approved by the network. You want to see the chances of that happening today [laughs]? We thought it was damn difficult then. We had to get nine shows in advance, three nines making 27. Or 28. The only way you can afford to go overseas is to get that many shows approved in advance and go shoot exteriors for all nine shows. Or some exteriors for all nine shows. Some or most. You do this three times a year. IA was perfectly happy to do it. Relations were fine, as far as I know, from top to bottom. Never any kind of labor problem.

But it meant you had to send one person, or one person with an assistant, in advance of you by at least a month to go from country to country and line up all your locations. Lock them down, get them signed and sealed, then get back and get them approved by the boss, by Mr. Leonard. And when he had approved all of that, we got on an airplane and we went.

And the other key to this was Fouad Said, a kid who was an Olympic-class swimmer from UCLA, walked into Sheldon’s office with an idea about turning a James Bond cigarette lighter into a studio. No, taking a little tiny Ford van and making little weird compartments in it to hold everything you need for a studio on wheels. This was the beginning of Cinemobile, and that’s what he named it. And each year, for the three years that we worked, he would come in with a slightly bigger van, slightly overhauled. Fouad was a genius, and is a billionaire today. The kid worked so hard that he put himself in a sanitarium at the end of the first year, because he’d just been burning the candle at three ends.

So Fou definitely was part of the armament that put Sheldon in the field, then the deal with the IA, and then the approval of nine scripts in advance. You have to have all that going all at the same time, and you have to have a boss, somebody running things like Sheldon, who’s the best general who ever lived. That’s how it got done. And riding the crest of all this was Bill and me, pretending like it was just nothing.

FYEO: How did this reunion movie come about?

CULP: Bill started all this in 1987. In 1987 he called [Daily Variety columnist] Army Archerd and told Army that we were gonna do I Spy at Warner Bros. as a big screen feature. So we embarked on a long, two and a half years, career with Warner Bros. We developed two screenplays, they developed two screenplays. We hated theirs, they hated ours. End of story.

FYEO: Did you do the writing on yours?

CULP: Yeah. Yeah, it was shocking. They talk about creative differences and usually it’s something else, personality differences or something like that. This was real creative differences. It wasn’t even the money part of it, because when they submitted their two scripts to us they approved of this first draft, they were ready to go forward. And they were terrible. Bill and I shot the first one down together, and then Bill shot the second one down from the hip, before he even talked to me. And we kept after it and after it and finally they realized that their costs, in renewing the option they had taken were huge. They got it for very little but to renew was a big bump. And they said, these guys don’t agree with us, we don’t agree with them, its not going anywhere, I think we’d better scrub this. And that was the end of that and it all went into limbo for a while.

FYEO: Then the project went to television?

CULP: Four years all this is going on, Jeff Sagansky at CBS hears about this and he just zeroes in on it like a bulldog. He said I want it, I want it for CBS, find a way to do it.

FYEO: Again two scripts were written, one of them yours. And the network rejected yours and chose the other, so you went into this project rather dubious about the script.

CULP: I was very dubious about it. But I said I’m going to leave all my judgment up in the air. Because I want to do this, Bill wanted to do it, if I don’t do it now he’ll never do it again. This is the last chance we’ll ever get. Somebody made a wrong call somewhere. But maybe they didn’t, maybe there’s something I don’t understand. So we got over there and what happened was, Bill and I fell into a pattern.

I wrote seven I Spys, I wrote more for I Spy than anybody did, and on top of that I rewrote most of them, verbally, on our feet while we were working... we’d go on stage and we’d try to mess around with it, with the help of the director, and finally with the agreement and forbearance in some cases of very talented directors. We’d decide where the camera should go first for the master, then Bill and I would go to work and everybody else would light the shot, and by the time they were finished lighting, which was somewhere between 20 minutes and half an hour— and if they saw we were in trouble they’d stretch it a little— we’d be ready.

I would suggest this, or I would write a scene down, Bill would rewrite it, we’d take both of those things together, work it around in the scene, in rehearsal a couple of times, then throw the whole thing away and whatever came out, came out. And it never came out twice the same way.

Bill keeps saying I taught him a lot of stuff. The only thing I really tried to teach him was always remember to try and feed the right cue to the other actors because they don’t know what the hell we’re doing. That’s the way we did I Spy. There wasn’t any other way to do it. Some people were not thrilled, but they put up with us because the end result appeared to be working.

FYEO: How does that compare with the new movie?

CULP: Exactly the same. Bill would start off here and go over there, I’d follow him. Then I’d get an idea and go over here and he’d follow me. Pretty soon we’d figure out what the scene was about and we’d improvise the whole thing. So the fact that the scenes did not work — in my humble opinion — didn’t affect Bill and me at all. We just whaled and went through. And sort of made it up as we went along. Like always.

FYEO: And did that make it fun?

CULP: Yes, it was a lot of fun. It was pure joy, the working process was pure joy.

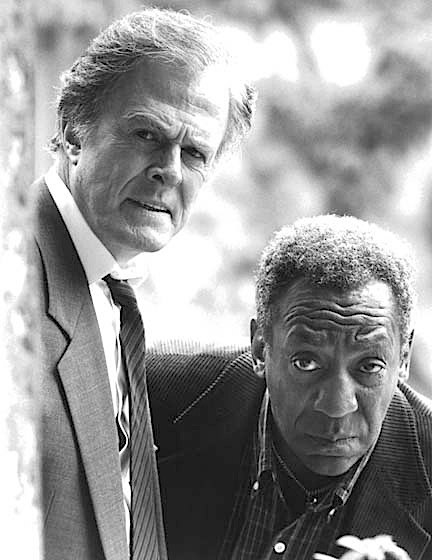

CBS finally aired “I Spy Returns” (pictured below) on Feb. 3, 1994, to a resounding thud.

Originally published in For Your Eyes Only #31, Sept. 1993